By 1643 they are desperate, and pray to the Virgin Mary to return good health to Lyon. Miraculously, the black plague disappears from the city, never to return and the people never doubt their divine protection.

So, how did the celebration of the Virgin Mary’s eradication of the plague become the largest light festival of our modern-day century?

|

| Lyon Skyline during the Light Festival |

It began on September 8th 1852, with the inauguration of the statue of the Virgin Mary, installed on La basilique Notre-Dame de Fourvière to thank her for banishing the plague from Lyon. Severe flooding prevented the festivities from taking place and the event was postponed to December 8th, and the Lyonnaise people showed their gratitude by lighting candles on their windowsills. As the years passed, this spontaneous jest increased in popularity to become, today, a grandiose festival of light.

During the 1980s, in conjunction with the advent of the ‘lighting plan’, the city of Lyon decided to transform the December 8th festival into la Fête des Lumières (light festival). Each year, the city’s public places would be illuminated in a different fashion, this coloured symphony of light bathing urban Lyon on the eve of the winter solstice.

My first light festival was in the year 2002. Anticipating large crowds, we opted for the train into Lyon centreville, descending into the cold night at St. Paul station in the Vieux Lyon. Restaurants lining the cobblestone streets blazed with lights, diners’ chatter and busy waiters. Tantalising aromas of frying garlic, butter and parsley mingled with the fog.

Crossing the Saône River we first glimpsed the illuminations on Fourvière Hill, where the Romans set up camp in the first century B.C. and where, atop the hill, Fourvière basilica was built between 1872 and 1884. Illuminated in alternate shades of green, blue and violet, the fortress basilica was transformed into a haunting, spectral tower.

|

| Light Festival, Lyon |

On Place des Terreaux, a group threw and swallowed fire for an enchanted audience, ‘ohs’ and ‘aahs’ echoing into the wintry darkness as flames leapt dangerously close to the performers. Then the old stones of the square melted into a cinematic screen of stars and moons. Coloured lights and shapes danced on a stage of renaissance architecture, a bloodied revolutionary soldier crept stealthily across the starry sky, and all sense of dimension was lost.

On Place Paul Chenavard, 15th century St. Nizier church was painted in stripes of dandelion yellow, orange and blue lights.

The temperature dropped, the night thickened with visitors and stall holders cried out: ‘Crepes, saucisson, vin chaud!’.

‘This moving public is at the heart of the festival,’ said the festival’s artistic director, ‘just as it is at the heart of urbanity, each person being a vector of light within the nocturnal landscape.’

At the old printing museum, high on an old stone staircase, children were mesmerised by a mediaeval play of sword–slashing and fierce shouting.

‘The very identity of Lyon is revealed in the light festival,’ said the mayor, ‘through an event that is both a popular event and a tribute to art and architecture through the use of light.

|

| Place Bellecour, Lyon. Statue of King Louis X1V |

On the stone floor of the Trinity Chapel in Lyon’s 2nd district, 2,000 white glass jars filled with water and blazing oil were distributed in wave forms to create the Equinoctial tide. French baroque music interpreted by three sopranos and an organ accompanied the lighting and extinction of the fires.

The city’s ancient weaving industry and textile production were revived through light projections onto the imposing St Jean Cathedral, invoking the weavers’ mechanisms and gestures. To complete the picture, a green laser beam linked St. Jean Cathedral to Fourvière Basilica.

Since its origin in the XIX century, December 8 has taken on an undeniably futuristic allure. But despite these magnificent illuminations, the Lyonnaise people never forget that the soul of the light festival remains within the beauty of thousands of tiny candle flames burning in unison, on windowsills.

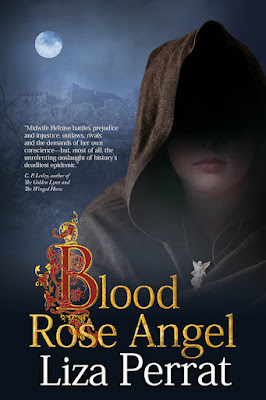

To celebrate the December 8th Light Festival, my mediaeval novel, Blood Rose Angel is on PROMO for only 99c/p.

Blood Rose Angel is the 3rd (standalone) novel in my French historical trilogy: The Bone Angel.

1348. As Bubonic Plague makes its first inroads into Europe, medicine, religion, family traditions and love intertwine in a woman’s search for identity and her battle to heal the sick in a world ruled by superstition.

Get your copy for only 99c/p HERE

Sign up for news of my new book releases and receive a FREE copy of Friends & Other Strangers, my award-winning collection of Australian short stories.

http://www.lizaperrat.com/

If you enjoy my books, follow me on BOOKBUB

.jpg)

.jpg)